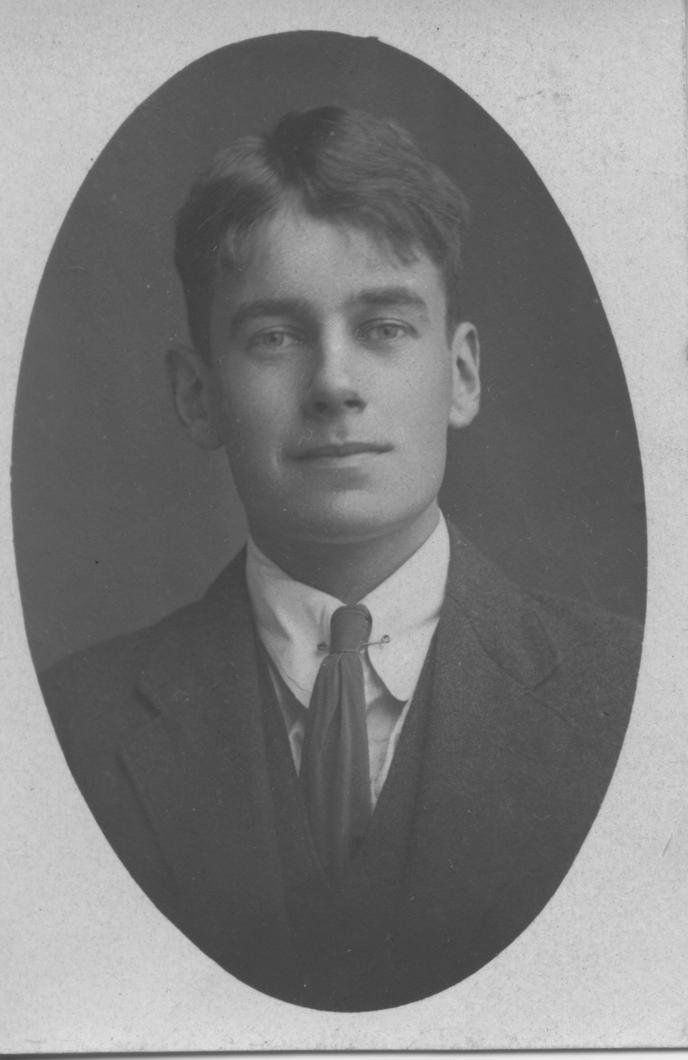

Hubert Butler

A Kilkenny native, Hubert made his name both as a respected essayist and a keen humanitarian—travelling to Nazi Austria to help save Jewish people from concentration camps.

Towards Vienna

Scholar, teacher, writer, and traveller, Hubert Marshall Butler was an Anglo-Irish Protestant born in Kilkenny in 1900. He passionately encouraged pluralism in Ireland, and was one of those rare individuals who really made a difference. Butler has often been described as “Ireland’s moral conscience”.

In the spring of 1938, Butler read a newspaper report of a protest meeting in the Mansion House, London, discussing the plight of European Jewry. The Archbishop of Canterbury spoke of “the systematic persecution without parallel even in the Middle Ages and the incredible mental and moral torture” to which Jews in Germany were being subjected. Subsequently, Butler went to work with The Religious Society of Friends at the Quaker International Centre in Vienna.

Butler worked closely with Emma Cadbury in the Vienna Centre, processing the paperwork of Jews and others desperate to obtain exit visas. Between 1928 and 1939, the Vienna Centre handled over 11,000 applications affecting 15,000 people. The centre managed to help over 4,500 people settle in other countries. During Butler’s time at the Quaker International Centre, he and his colleagues helped 2,408 Jews leave Austria.

Soon after he arrived in Vienna, in July 1938, Butler attended the Évian Conference on Refugees. There, he discovered that no country was prepared to offer a safe haven for Jewish or other refugees from Nazism. Butler returned to Vienna furious and disheartened. In Stemming the Dark Tide, Sheila Spielhofer gives an insight into the huge task facing the Vienna Centre: Faced with apparently insoluble problems and living in a country where hatred, intolerance and violence seemed to triumph, the workers at the Centre as well as the Vienna Group were in danger of falling into a state of despondency and inertia.

Butler often reflected on the way people react to evil. In The Children of Drancy, he writes: Hitler brought into the world misery such as no man had previously conceived possible. It had to be combated. The British were slow to observe this. The Irish never did.

Young Hubert Butler

“Butler attended the Evian international conference on the plight of Jewish refugees in July 1938 and was sickened by the attitudes of the Irish delegation, one member of which said to him: ‘Didn’t we suffer like this in the Penal days and nobody came to our help?’”

- Fintan O’Toole, The Irish Times

The Kagran Group

At the Centre, Butler helped set up The Kagran Gruppe (group), an agricultural co-operative of Viennese Jews and people whose Jewish connections were only partial, such as a Jewish spouse or grandparent, who had banded together for collective emigration.

Every morning, the members of the group took the long tram journey to Kagran, a suburb on the banks of the Danube. There they worked under the supervision of Gestapo guards, who were amused at the sight of middleclass Jews, including elderly people and children, who had never held a shovel before, toiling at heavy manual labour.

Meanwhile, Butler and his colleagues tried desperately to get entry permits for the Kagran Group as migrant workers to Peru, Bolivia, Rhodesia, Colombia, Canada, England and Ireland. The Kagran Group became a vehicle by which approximately 150 people obtained exit permits from Austria. Ultimately, very few members of the Kagran Group actually settled in Ireland. Most of them put down roots and remained in Britain.

Butler was instrumental in creating the Irish Co-ordinating Committee for Refugees. This was a cross-section of highly regarded Irishmen from both the Catholic and Protestant traditions working together. They attempted to secure temporary settlement for refugees in Ireland.

In 1988, Butler published The Children of Drancy, the title of which was inspired by the infamous transit camp outside Paris from which thousands of French Jewish children and adults were packed into cattle trucks in the summer of 1942 and deported to Auschwitz.

“Hitler brought into the world misery such as no man had previously conceived possible. It had to be combated. The British were slow to observe this. The Irish never did.”

— Hubert Butler, The Children of Drancy

Post-war Ustaše findings

Information about the Holocaust reached Ireland during the war years, and the Chief Rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine (and former Chief Rabbi of Ireland), Isaac Herzog, sent telegrams throughout the war to Éamon de Valera, expressing the urgent need to take in refugees. But, as Butler had noted, the mood in Ireland was one of ignorance and indifference.

After the war, Butler’s concern for injustices towards others prompted him to investigate the wartime genocide conducted by the viciously anti-Serb Orthodox Christian and antisemitic Ustaše regime in Croatia. In particular, he highlighted the case of Andrija Artukovic, the former Croat Minister of the Interior, whom the Yugoslavs were trying to have extradited from the US for war crimes. Like so many other former members of the Nazi-sympathising Croatian government, Artukovic was helped to escape by powerful interests, including Roman Catholic clergy. In documents shown to him in New York, Butler discovered that Artukovic had also spent time in Ireland in 1947.

During a public meeting in Dublin in 1952, Butler’s denunciation of the ecclesiastical role in the Ustaše genocide led to a walkout by the Papal Nuncio. Butler and his family were ostracised, and he was forced to resign from the Kilkenny Archaeological Society, which he had founded. At the Butler centenary in October 2000, the mayor of Kilkenny finally apologised publicly for the failure to acknowledge Butler’s account of the truth, all those years earlier.

In his long life of 91 years, Hubert Marshall Butler was a staunch advocate of truth and justice. He became champion of many who had suffered injustices, and will be remembered as a great humanitarian.

Hubert and Peggy

Witness to the Future

Directed and produced by Johnny Gogan of Bandit Films, Witness to the Future is available to watch on Netflix.

The documentary features interviews with John Banville, Julia Crampton (daughter), Olivia O'Leary, Robert Tobin (biographer), Chris Agee, Fintan O'Toole, Roy Foster, Lara Marlowe, Joe Hone, Suzanna Crampton (granddaughter), Dr. Michael Kennedy, and Antony Farrell.

“Butler was fifty years ahead of his time.”

— Olivia O’Leary

Learn about other heroic Irish people

-

Mary Elmes

-

Msgr O'Flaherty

-

Dr Bob Collis